Krakow November 2005

The ‘new’ jewish cemetery. The earliest graves are from the 1840s. An older medieval cemetery also exists in Krakow – The Remuh, which was founded in 1553. Walking down this corridor of the cemetery I noticed that many of the headstones indicate dates of death in 1942, 1943 and 1944

On my various trips to Poland what has always struck me is how well individual graves are maintained and regularily visited by family members. The jewish cemeteries present a different story however – broken and overgrown graves and little evidence of the detrius of family visits.

On the winter’s day I entered the cemetery the caretaker greeted me in German – informing me that the cemetery was about to close.

Rathausufer 18 Düsseldorf-Altstadt; Reisel & Pescha Birnbach – from the inscription Reisel & Pescha were evicted rather than being deported – though their eventual fate was ‘murdered’

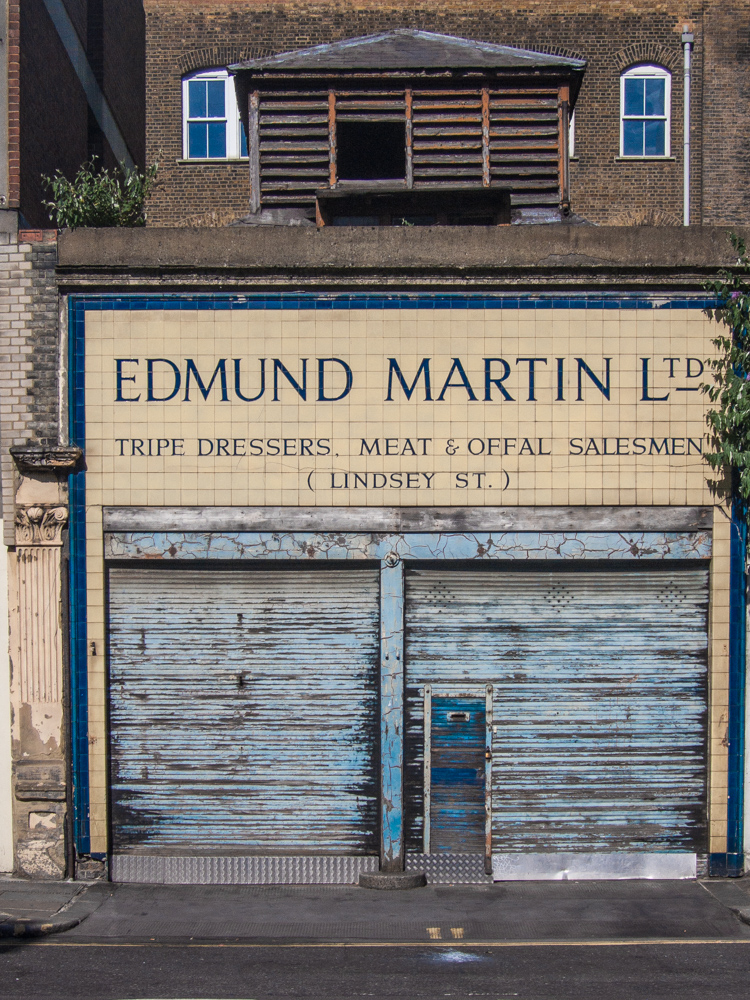

Kreuzberg Berlin

Stolpersteine – Naunynstrasse 46 Kreuzberg Berlin; Siegfried & Edith Robinski

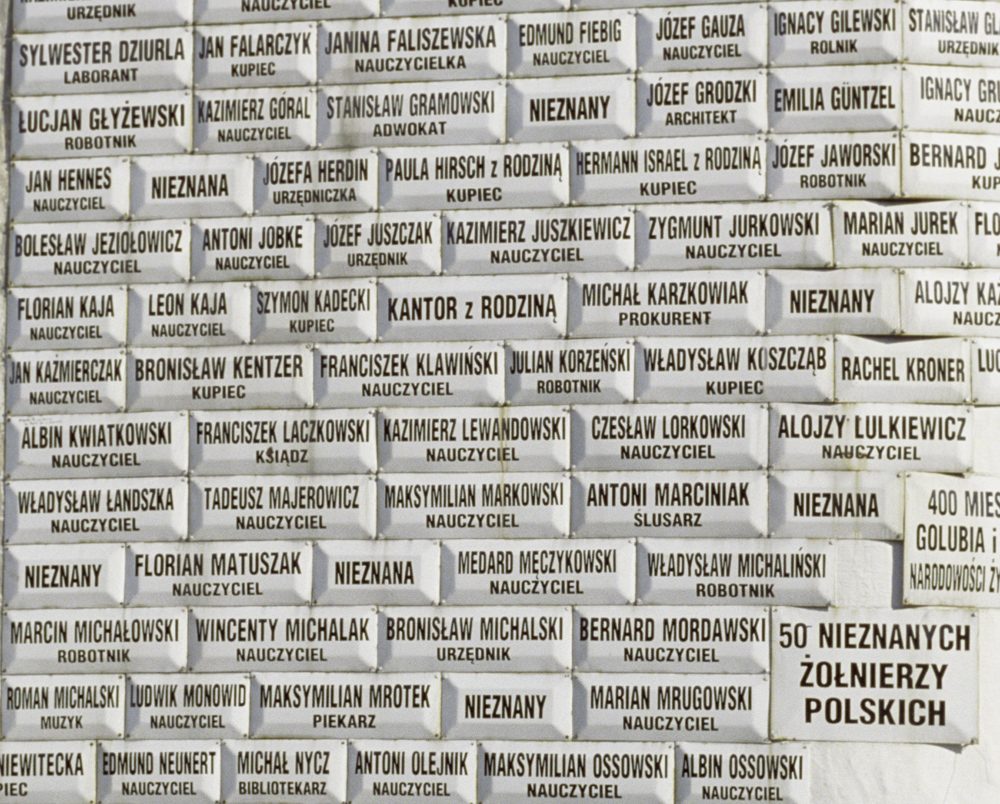

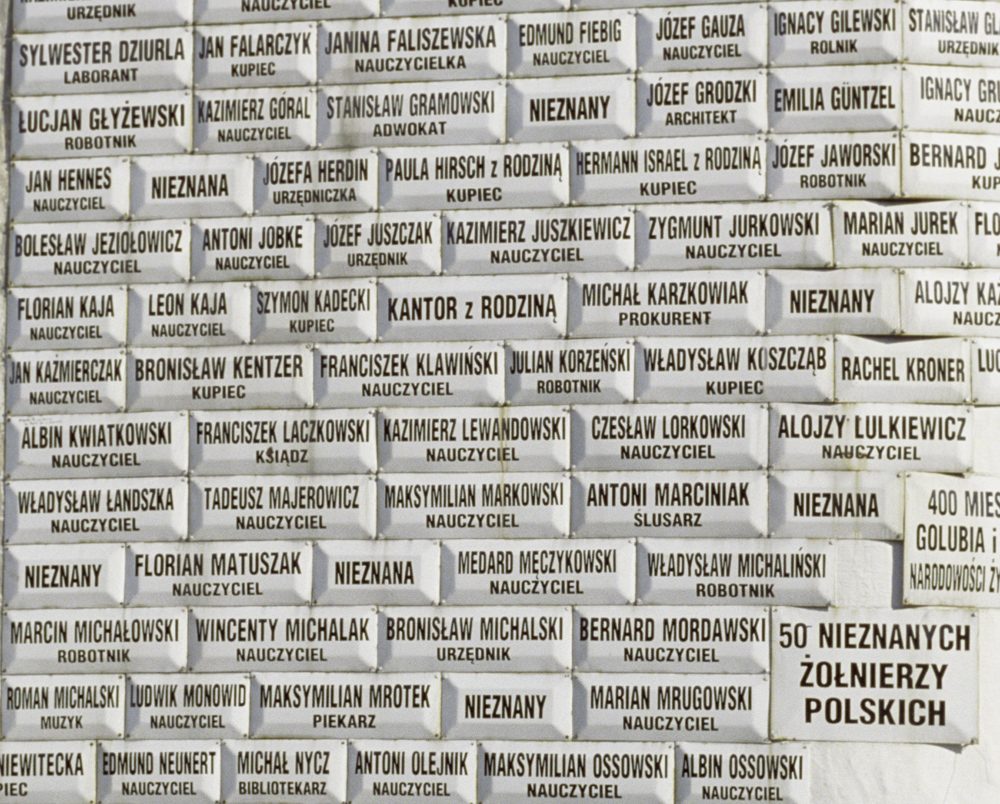

This memorial in Fordon, Poland, marks the site of the Dolina Śmierci (valley of death) where 5,000 – 6,000 local residents were murdered in 1939. The panels on the memorial, which list just name and profession, reflect the lists compiled before the war, which sought to eradicate the doctors, lawyers and priests of a generation.

The Rhine from Rathausufer Düsseldorf-Altstadt

Stolpersteine Rathausufer 15 Düsseldorf-Altstadt; Alfred & Meta Meyerstein

Rathausufer 15 Düsseldorf-Altstadt

The church interior is a burnt out shell – damaged at the end of world war 2. Abandoned for many years it is slowly being restored.

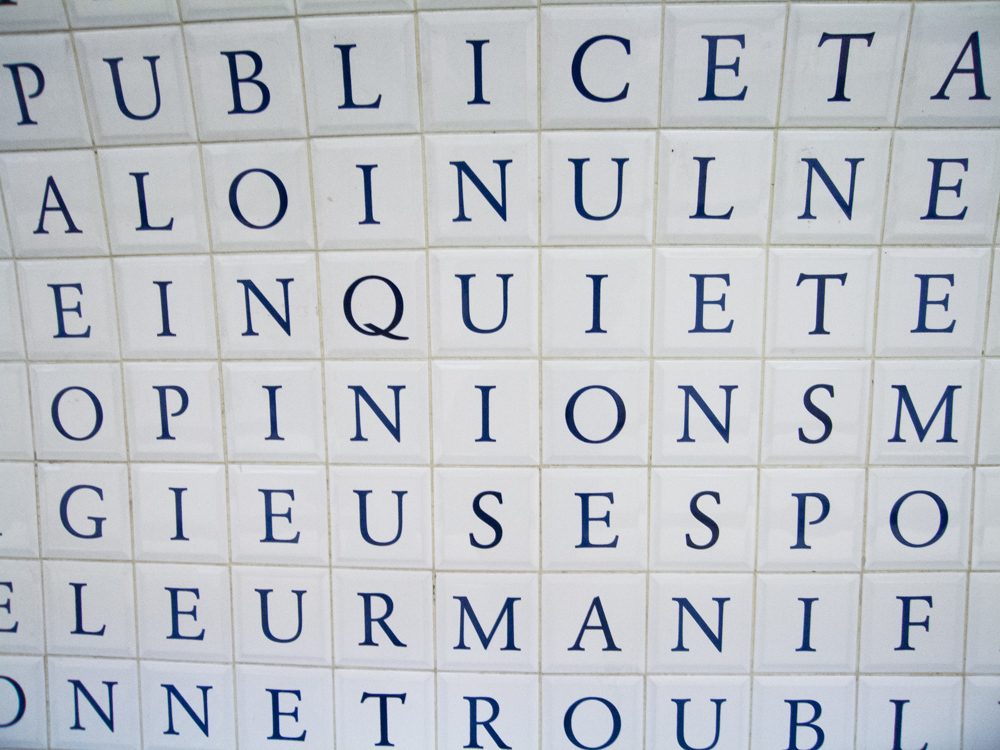

Of the three planned facades of the Sagrada Familia only the Nativity facade to the east was completed during Gaudi’s lifetime. Work on the passion facade commenced in the 1950s and was only completed in the late 1970s. It has an austere and stripped back design – symbolising the passion and death of Jesus. While the passion facade follows the general outlines of Gaudi’s design the details – most notably the sculptures by the Catalan artist Josep Maria Subirachs – bring another layer of individual style to Gaudi’s last project.

The genesis of this project arose out of my first visits to Poland in 2005 and the stark differences I discovered between the Polish Catholic cemeteries and the state of the Jewish cemeteries in Krakow. It was not just the overgrown, cracked and broken tombstones – but also the years of death on many of the tombstones in the Miodowa Street cemetery. Then there is the absence of the detritus of visits by family members to the graves – clearly evident in other Polish cemeteries. It is this last visual clue that reminds us that in less than six years a rich and varied Jewish culture, which had existed for 600 years, was eradicated.

The statistics of those who were displaced seem beyond imagination – yet they involve countless individual lives and histories. The ‘Stolpersteine’ (Stumble Stones) project by the German artist Günter Demnig, is just one small step to assimilate this enormity into individual personal details. ‘Stumble Stones’ are small brass plaques lodged in the pavement next to the homes of those deported. Each plaque indicates the name, year of birth, date of deportation, and eventual destination of each individual. Sometimes whole clusters of these stones can be found where entire apartment blocks were evacuated of their inhabitants.

In the Polish city of Bydgoszcz at Fordon a memorial marks the site of the Dolina Śmierci (valley of death) where 5,000 – 6,000 local residents were murdered in 1939. The panels on the memorial, which list just name and profession, reflect the lists compiled before the war, which sought to eradicate the doctors, lawyers and priests of a generation.

These physical memories remind us that within the grand historical narrative lie the stories of ordinary people and everyday lives.

The burnt our shell of St Johannes church in Gdansk and the half-finished Sagrada de Familia in Barcelona are both reminders of the interruptions and dislocation of war and the distortions of fascism which has left its mark in cemeteries, cities and pavements across Europe.