Rathausufer 18 Düsseldorf-Altstadt; Reisel & Pescha Birnbach – Reisel & Pescha were evicted rather than being deported – though their eventual fate was ‘murdered’

Rathausufer 18 Düsseldorf-Altstadt

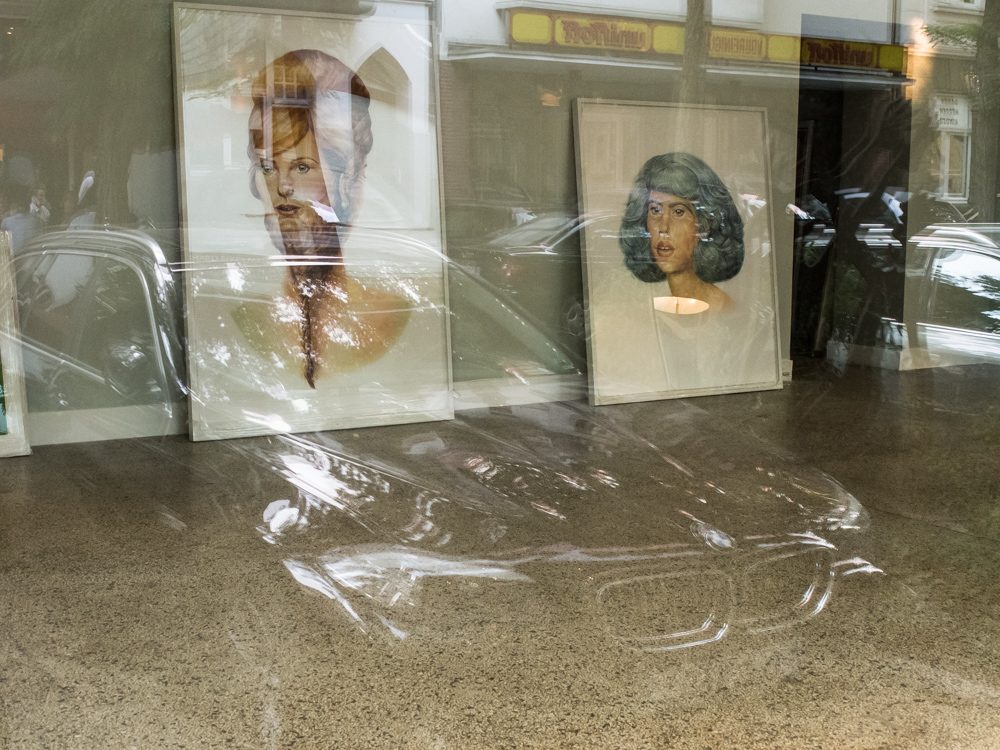

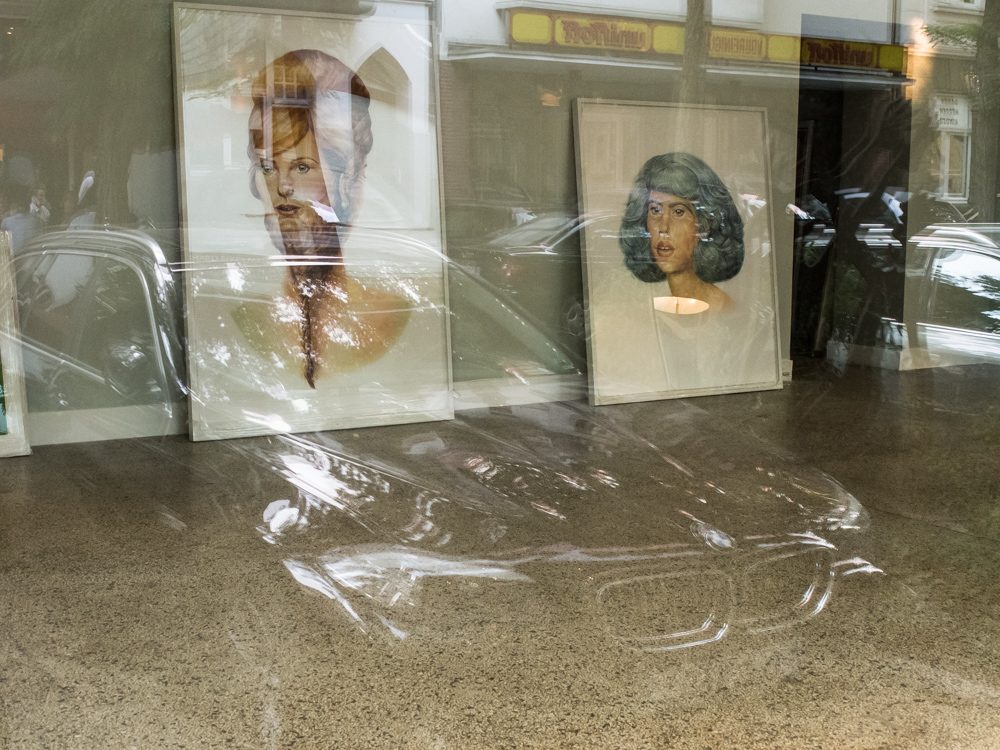

Düsseldorf – Altstadt

Rathausufer 15 Düsseldorf-Altstadt; Alfred & Meta Meyerstein

Trinkhalle – Dusseldorf

Konrad-Adenauer Platz 1 Düsseldorf; Eduard & Hanna Wolff

Immermannstraße 71 Düsseldorf; Otto & Frieda Baum, Julo Levin & Grete Rothschild – Grete fled to France but was deported and murdered in Auschwitz

Düsseldorf Hauptbahnhof

Stresemannstraße 29, Düsseldorf

Stresemannstraße 30, Düsseldorf; Seigfried, Elfriede & Hanna Bella Schott

Stresemannstraße 35, Düsseldorf

Oststrasse Düsseldorf-Stadtmitte

Leopoldstrasse 22 Düsseldorf-Stadtmitte

Leopoldstrasse 22 Düsseldorf -Stadtmitte; Franz Monjau. He was hidden in 1944 and eventually deported and died in early 1945

Oststraße, Düsseldorf

Oststraße 52, Düsseldorf

Josephinenstrasse Düsseldorf

Josephinenstrasse 13 Düsseldorf; Benjamin & Martha Baer

Blumenstrasse 9 Düsseldorf; David and Johanna Altmann

Königsallee Düsseldorf

Königsallee 86 Düsseldorf; Hulda Hornstein and Walter Erle

Nordstraße, Düsseldorf

Nordstraße 3, Düsseldorf; Gerhard & Klara Wahrenberg

Am Wehrhahn Düsseldorf

Am Wehrhahn 5 Düsseldorf; Otto, Frieda, Ingeborg, Gunther Leo and Herbert Schwarz

Worringer Straße 12 Düsseldorf; Felix Klees – arrested, sabotaged and then shot

Worringer Straße Düsseldorf

Worringer Straße 58 Düsseldorf; Rudolf Ems – Rudolf died before being deported

Graf-Recke-Straße 49 Düsseldorf; Arthur and Anne Cohen

Graf-Recke-Straße 49 Düsseldorf

Graf-Recke-Straße 53 Düsseldorf; Reinhard Semrau – harrassed by the Gestapo he was killed whilst trying to escape

Lindermannstraße Düsseldorf

Lindermannstraße Düsseldorf

Fürstenplatz

Tat’s Furstenwall, Düsseldorf-Friedrichstadt

Corner Furstenwall & Jahnstrasse Düsseldorf-Friedrichstadt; Adolf & Frieda Baumblatt

Kirchfeldstrasse 87 Düsseldorf-Friedrichstadt; Georg Gehring – Georg was arrested in 1943 and shot in 1944

Kirchfeldstrasse

Kirschfeldstrasse Düsseldorf-Friedrichstadt

Kirschfeldstrasse 145 Düsseldorf-Friedrichstadt; Henriette Lion

Friendenstrasse 18 Düsseldorf Friedrichstadt; Siegfried Steinberg. He was arrested in 1935 and shot in 1941

Friedenstrasse 18 Düsseldorf-Friedrichstadt

Düsseldorf-Friedrichstadt

Düsseldorf – Hafen

Düsseldorf-Oberkassel

Cheruskerstr. 99, Düsseldorf; Eugen, Henriette & Ilse Neumark

Cheruskerstrasse 44 Düsseldorf-Oberkassel

Cheruskerstrasse 44 Düsseldorf-Oberkassel; Sophie Markus

Wildenbruchstrasse Düsseldorf-Oberkassel

Wildenbruchstrasse 107 Düsseldorf-Oberkassel; Max Dannenbaum

Luegallee 15, Düsseldorf; Else Bernstein & Paula Freund

Luegallee, Düsseldorf

Rochussstrasse 7 Düsseldorf-Pempelfort

Rochussstrasse 7 Düsseldorf-Pempelfort; Karl Robert Kreiten. Karl Robert was executed in Berlin in 1943

Julicherstrasse 5 Düsseldorf-Derendorf

Julicherstrasse Düsseldorf-Derendorf

Julicherstrasse 5 Düsseldorf-Derendorf; Wolf, Ellen & Fanny Frank

Schillerstraße Düsseldorf

Schillerstraße 65 Düsseldorf; Margarete Frochtling

Paulusstraße 15 Düsseldorf; Josef Herkenrath. Placed in detention and died in 1942

Uhlandstrasse 23 Düsseldorf

Uhlandstrasse 23 Düsseldorf; Hedwig Jung-Danielewicz

Düsseldorf-Eller

Gumbertstrasse Düsseldorf-Eller

Reisholzerstrasse 28 Düsseldorf-Lierenfeld

Reisholzerstrasse 28 Düsseldorf-Lierenfeld; Hans, Anna, Herbert & Marianne Neubeck. The family fled to Belgium in 1935. Hans died in the Spanish Civil War and Marianne & Anna were deported to Auschwitz. Herbert was arrested and executed in Berlin in 1943

Düsseldorf-Eller

Dusseldorf Eller

Ludenbergerstrasse 37 Düsseldorf-Grafenburg

Ludenbergerstrasse 37 Düsseldorf-Grafenburg; Alma Fuhrmann

Ludenbergerstrasse Düsseldorf-Grafenburg

Düsseldorf – Burgplatz

Cecileneallee 11 Düsseldorf; Franz Anselm Cohen-Altmann – Franz was removed to a psychiatric hospital but later died…

Ursulinengasse 7 Düsseldorf – Altstadt; Karl Jung

Ursulinengasse 9 Düsseldorf – Altstadt; Johann Wilhelm Adloff. From the inscription we know that Johann was a resident of mental institutions from 1921 but was then moved in 1941 to Bernburg, one of the locations where the mentally ill, disabled and other ‘undesirables’ were gassed under the Aktion T4 programme.

Ratinger Strasse

Graf-Adolf-Str. 16, Düsseldorf; Oskar, Ruth, Max & Uri Mainz

Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf – Altstadt

Düsseldorf – Hafen

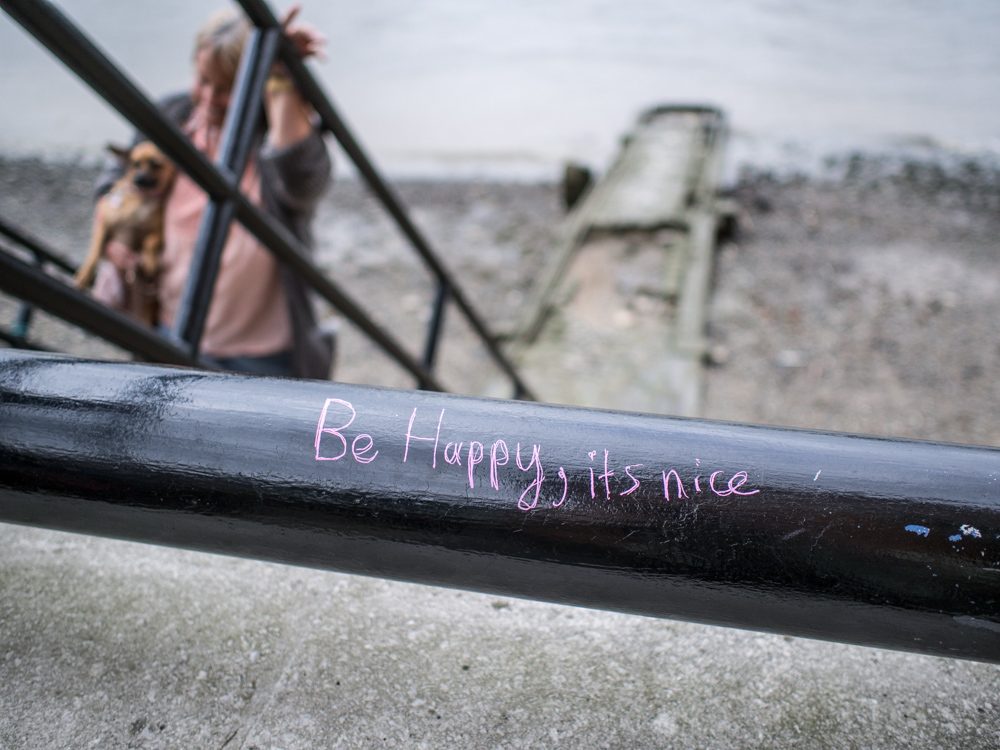

These small brass plaques, lodged in the pavement, are a reminder of the countless individual lives that make up the clinical statistics that confound our ability to assimilate the horror of the millions who died under Nazi ‘re-settlement’.

My initial introduction to the Stolpersteine project was during a visit to Berlin in the summer of 2006. Two ‘stumble stones’ in the pavement at Naunynstrasse in Kreuzberg struck me as a far more compelling reflection on the impact of the Shoah than memorials to the factories of death. The idea is simple – each ‘stone’ includes the name, year of birth, date of deportation, eventual destination and fate of individual residents who once lived in the building – ‘Hier Wohnte’. The project is the work of a Köln based artist, Gunter Demnig.

The project began in Köln in 1994, later spread to Berlin-Kreuzberg, and has since expanded to other German, Austrian and European cities. At last count more than 40,000 Stolpersteine have become part of the pavement – a persistent reminder of those who were displaced. Funding comes from a variety of sources, which includes donations and sometimes requests from surviving family members. Each stone costs €120.

As the project has evolved it has come to encompass the often forgotten Gypsies, Poles, Political Dissidents, Catholics and other ‘undesirables’ who disappeared in the Nazi camps.

Much of my exploration of the work of Gunter Demnig has focussed on the city of Düsseldorf, which I visit frequently. I wanted to present the Stolpersteine but also the surrounding streetscape – the environment in which the departed lived. As I’ve walked across the city, from the Altstadt by the Rhine to the old working class district of Eller, I’ve often literally ‘stumbled’ across a new stone set in the pavement. More recently I’ve also explored other cities – you can see my visit to Aachen here

As we stumble across the ‘stones’ we can see that some have been in place for several years – becoming part of the pavement with their softened corners and the marks of the revolving cycles of the seasons. With the more recent ‘stones’ one can still see the evidence of the hand of Gunter Demnig in the disturbed pavement and the new clear brass.

The inscriptions on the stolpersteine suggest a variety of subtle readings. Among the early dates of those removed is the word, ausgewiesen, indicating that the individuals were ‘evicted’, rather than deported – later, deportiert is used exclusively, reflecting the evolution of Nazi policy toward a final solution for its ‘undesirable’ citizens. Then there is the use of either ermordet, ‘murdered’ or tot, ‘died’ – a bureaucratic distinction between those who died of disease, overwork or lack of food in the camps and ghettos and those who were gassed or killed through some other active means.

Other inscriptions reveal those who left or escaped ‘flucht’ and were later deported from elsewhere; those who were hidden ‘versteckt’ and later deported, as well as those arrested and executed – presumably for political crimes. On my most recent visit to Düsseldorf in the summer of 2013 I stumbled across one Johann Adloff, one of the 200,000 or so we believe were killed under Aktion T4 – a euthanasia project to rid Germany of the physically disabled and mentally ill.